Introduction

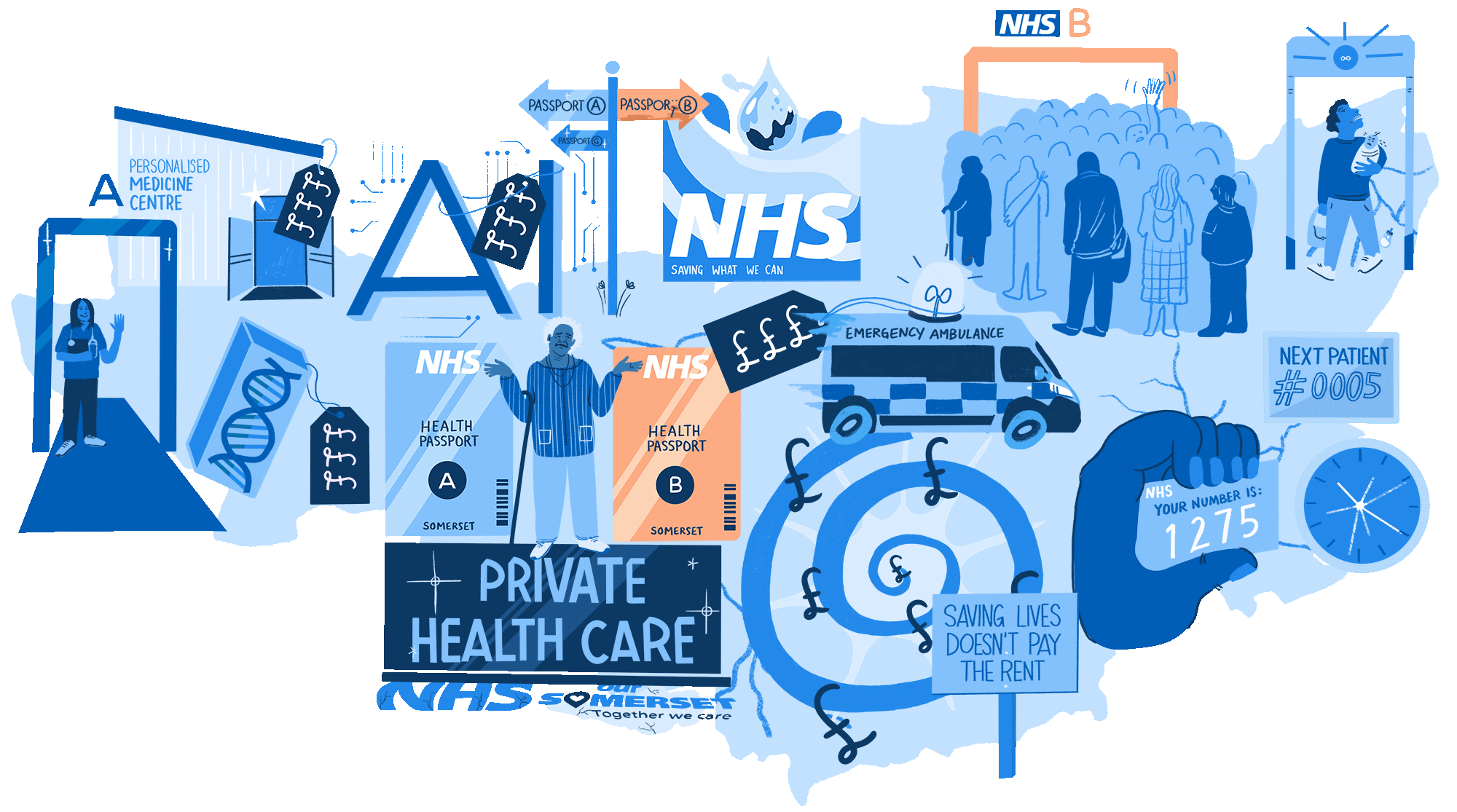

The Two-Tier Health and Care System scenario describes the consequence of a decade of increased health, economic and social inequalities in the South West coupled with a surge in private health care provision through technology. Those with the means do well in this scenario.

Those without must rely on an NHS that has been contracting for a decade through under investment and understaffing.

What will it be like in 2035?

Personalised care and treatments, specific to individuals, are available through privatised genomic centres across the South West - for those who can afford it.

Approaches such as whole genome sequencing, data and informatics, and wearable technology will be routinely used by private health care insurers and private health care providers.

30 percent of the population of Somerset - those without access to private healthcare - will totally rely on the National Health Service which is under resourced and understaffed in the South West

A divergence of health outcomes will be clearly evidenced between those relying on National Health Services and those with access to advanced private health and treatment services.

A view from 2035

Today in 2035, Somerset and the rest of the South West is divided across the fault lines of health, social and economic inequalities. In 2025, the Leader of the Opposition in a landmark speech in the Commons said,

It's time to face facts. The NHS we once knew and loved is gone. Patients can no longer expect the same level of care from our NHS. Only those with money can afford good health! Year after year, we have seen a betrayal of ideals that underpinned our once great NHS. We no longer have fair and accessible health care free at the point of delivery. Colleagues, The NHS has been privatised by the opposition benches…

The vision of the 2023-2028 Primary Care Strategy in Somerset set out to achieve the following:

People in Somerset will experience primary care services that give them a warm welcome and are caring.

People working in our primary care services will have the time and space to do a professional job, responding to what matters to patients.

Primary care services will be local, effective, and comprehensive.

People will be able to access care when they need it.

In 2035 we see a workforce that still wants to meet these aspirations, but is unable to due to weeded-in inequalities that are part of the fabric of life in Somerset.

Across Europe, populist, right-wing governments are the norm where a narrative of intolerance to social state support has been replaced by a more fundamental, capital-based ideology. After the discontent of traditional political parties grew in the early part of the 2020s, new political parties have emerged in the UK feeding on the growing discontent of the masses, whilst ironically perpetuating the social divide between those who are financially wealthy compared with those who are poorer.

Today, the 1947 NHS legacy of free healthcare for all at the point of delivery still exists but in a significantly watered-down version. An adherence to traditional thinking and skills in relation to workforce planning hasn't led to an imaginative approach which could have transformed the system.

A basic level of care and service provision is available free at POD but there are long waiting lists to access even basic consultations and emergency services are limited. To access quality care, diagnostics and specialist services people now have to pay either through a tiered system built into the NHS or directly through the private sector. Politicians, NHS leaders and private sector providers blame each other and have done so for a decade or more.

Political promises following the great pandemic of 2021 vanished and although the initial fears of recession seemed to have dissipated, a combination of the continuing and attritional war in Ukraine, the impact on energy prices and the overall cost of living contributing to rising inflationary pressures, a spiral of economic crises led to ongoing recessions. Pension funds collapsed, taking away the retirement many in Somerset and the rest of the South West had hoped for. Added external and often unexpected pressures, such as climate change impacts where there is an increased prevalence of natural disasters such as coastal flooding, heatwaves and bitter winters, can contribute to a state service that is struggling to cope.

There have been years of underfunding in the NHS. Instead of direct investment, consecutive governments relied heavily on the private sector to invest in research, development and technology. After a time, governments could no longer afford the inflated prices of the private sector despite the combined buying power of the NHS to get commonly used products cheaper. The private sector began to dominate and by 2030 they had created a fully functioning private care system for those able to pay.

For those who have health insurance and can access the private care system in the South West, huge advances in pharmacogenomics allow doctors to target specific genetic / disease combinations with the most effective drugs. Gene-editing technologies have allowed some of the most intractable inherited genetic conditions to be treated, but only for those able to pay for it.

A digital health passport has become the primary source of access to services across the country and The South West Region has been an early adopter of the passport system, such that, by 2035 this is now firmly embedded as the sole mechanism for access to care.

In 2035, there are currently two passport tiers

Tier A

The Tier A passport which is blue coloured and has a range of visa permits which can be purchased by individuals or through employee schemes to access a broad landscape of services ranging from physical care to high tech diagnostics and digital interventions. Access is granted through a personalised QR code available to buy directly from Health providers or through the burgeoning health insurance market. Gold standard passports are also available to buy from national and global health companies allowing patients to travel freely within the UK and international health economy, facilitating greater choice and access to specialist expertise.

Tier B

The Tier B passport which is red coloured and has access only to NHS and state provided services. There is no prioritisation of access in the Tier B passport system and access to all services is managed through a first come first serve basis. It is available for services within the South West region only.

In 2035, NHS managers were instructed to stop annual planning cycles, previously used to ensure that service provision is available all year round. Instead today they are instructed to release new appointments and delivery schedules only at the start of each financial year and run services until the annual financial allocation has been used up.

In 2034 many services were stood down in September when resources were used up. Today, in March 2035, waiting list demand has already exceeded the 2035 resource allocation and appointments are being scheduled for 2036.

Emergency services responded to the scheduling crisis by automatically referring critical patients, for example, from RTAs and other immediately life-threatening incidents onto Tier A pathways to enable life-saving medical care. This has had a knock-on effect in the courts as reclaim departments set up new processes to legally address nonpayment. Today insurance companies are extending life insurance policies to include emergency care cover in the event of unexpected critical admission but those without cover now find their situation compounded by critical illness and a legal case for the care that saved their life.

In the early part of the 2020s, ongoing industrial action relating to pay settlements led to an erosion of trust and a feeling of disaffection amongst health and care staff. Salaries have been lagging behind inflation for many years, and the incentive to work in the state health service is very low, especially with more financially lucrative offers in the private healthcare sector.

The One Somerset Workforce strategy struggled to gain momentum in the early to mid 2020s. Many staff, who were furloughed in September 2034 on a 20% salary retainer on condition they returned to the service in 2035, have now joined private sector healthcare bank teams and have mostly resigned from the NHS. Pockets of innovation in the NHS which ran out of funding in 2034 were bought up or otherwise acquired by the private sector in order to keep them running. These are now only available to Tier A passport holders.

The South West state healthcare system is at breaking point and is regarded as no longer viable. This has been raised in the House of Commons by the local MP and an inquiry into future viability of the NHS has been set up, led by Lord Bruce Griffiths whose team has let it be known that the outcome is a foregone conclusion.

Reform of social services would mean more responsibility taken for the elderly by families and/or the community – where an old person has no support group and they become in need of residential care, they are taken into state care institutions. Stories leaked from these institutions are not good. The death rate is high from rampant infections which cannot be contained, and the ongoing waves of Covid-19 and its mutational variants has led to increased instability and unpredictability.

When an elderly person with no other support requires continuous health care they can only be admitted to a CDU (community hospitals are no longer available to the elderly).

The CDU is part of the basic NHS package so it is free. If you want a better level of care, the only option available is to access private health care which is expensive and only possible for those with relative wealth. An elderly person will only be admitted for a health issue once agreement and or means to pay have been ascertained and financial transactions have been made. As the population in Somerset of those over the age of 70 in 2035 has more than doubled since 2025, there is a real danger that those who are elderly and vulnerable are placed at significant risk.

In order to deal with the range of health issues, patient behaviours and lack of staff, units resort to mass sedation in order to manage volatile and unpredictable situations.

Palliative care is reduced to pain management with the 2020s criteria for Do Not Resuscitate stripped back to a Do Not Treat policy which is adhered to in every case admitted to the CDU. CDUs have become synonymous in the community with transit lounges to the morgue, and generally speaking only those elderly people with no advocacy support or no personal resources are admitted. In the wake of a cry to avoid a return to a 19th century poorhouse scenario, the insurance sector stepped in and a new insurance scheme for families with elderly relatives without financial resources has been set up to help meet the cost of private care. In 2035 the scheme is in its infancy and for those without private resources many older people are either admitted to the CDUs to die, or die alone, often lonely, forgotten and in pain.

Health brands closely associated with reputable tech organisations have continued to grow and they have made their influence felt across the sphere of health and wellbeing in scores of Personal Medicine Centres across the South West. People go there to be profiled and supported through life stages, accessing prevention medicines and regular screening. This is a world apart from those reliant on the NHS.

Many affluent young people have not gone to traditional universities to study, which have been dramatically devalued in recent years. They instead go, at a high cost, to highly sought-after privately-run learning centres - funded by multinational insurance companies which prepare young people with the required, adaptive skills for a career in private health care. When they enter the high-end of the labour market, young people from more affluent backgrounds have more choice, in terms of sector and region. The South West is seen as a good place to locate with a good life and work balance.

Affluent young people looking to join the NHS are well rehearsed in the kinds of jobs which Artificial Intelligence (AI) will create and which ones it will replace. Today in 2035, they are entering the world of work, demanding a new deal from employers. They know that they have skills which are in demand in health care. The pace of change in AI technology has seen a burgeoning industry in postgraduate and professional development learning centres. With the initial fears over the dangers of AI in the early part of the 2020s largely mitigated by effective regulation across global governments, those with such skills can expect the highest salaries.

At the fee-paying private schools across the South West, young people and their parents demand learning and tuition in computer science, software development and financial management. Soft skills are seen as important to the changing job market. Many young people aim to become self-employed and provide artisan bespoke services. For those attending schools in the state sector, there is a mixed quality of education. There are still opportunities, but it is a postcode lottery as to the school you attend and its specialisms. In some cases, talented young people are not able to access the same educational opportunities in a system that has become fragmented and two-tier in itself.

In the winter months, it is commonplace to see people struggling to get vaccines, queuing outside health centres in the South West to receive the annual covid and flu vaccines. Over the years, a number of Covid variants have emerged. Those who are able to afford Tier A blue passport health care will have been vaccinated as a matter of course; those Tier B red passport holders are often lucky if they are able to access vaccination at all, which is only available once blue passport holders have been served. The impact of Covid therefore continues to be seen amongst those who live in the more deprived communities of Somerset.

The Third sector is increasingly marginalised as a peripheral provider of non-urgent services which are now, by and large, run as community volunteer schemes with little regulation of training to shore up the well-intentioned spare time activities of an increasingly time and money rich section of society.

Some Third Sector organisations have created a niche in the market as a cheap provider of complex care services, taking on the service demands that public sector organisations are no longer able to manage. Individuals with complex care needs and comorbidities are referred into these services as a first step in any assessment process.

Large Third Sector provider consortiums are set up to gateway access to the healthcare market. These are managed by a South West Regional Programme Management Body (PMB) set up by a retired MacDonald Partner to coordinate and unify disparate third sector offers under one umbrella management company.

The Third Sector organisations who initially resisted this move to homogeneous management have now folded, as diverse sources of funding dried up in the early 2030s. The remaining providers are motivated by organisational survival in some cases and entrepreneurial zest in others who have entered the third sector space as a way to acquire less desirable services.

The increasing distance between regulation and Third Sector provision means that quality and safety standards are now less important as an aspect of the work; a greater priority is containing service users so that demand on public sector services is minimised and adhering to strict management procedures from the Programme Management Body in relation to budgets and accountability.

Rising inequalities across society at large are now perhaps most strikingly crystalised in the increasingly divergent life expectancies of people living in different parts of the South West Region. Within larger towns and cities such as Bournemouth, Plymouth and Bristol, life expectancy now varies by as much as ten years between poorer and more affluent postcodes; a 65-year-old woman living in mid-Devon or the Cotswold District, meanwhile, can expect to live for an additional twenty-four years based on local averages. In Somerset, similar health equalities are clear to see.

In 2020, life expectancy for men was 5.5 years lower and 4 years lower for women in the most deprived areas of Somerset than in the least deprived areas. Now in 2035, that has risen to 12.2 years lower for men and 8.1 years lower for women in the same SIMD demographic.

Overall, the data indicates that wealthier residents of the South West are now likely to have some of the lengthiest lives in Europe. For those with money, it is an enjoyable extended life; for those with little money, it can be an ordeal to endure. Life expectancy in Somerset in 2023 had increased by around two years in the previous 15 years, with men expected to live until 80.5 years and women 84.1 years. This remains higher than for the national average and as life expectancy increases, the time spent in ill health also increases. By 2035, this had increased further to 82.5 for men and 84.6 for women. In 2035, it is expected that the last 20 years of life will be spent in ill health - being overweight and obese remains an issue with 62% of the population of Somerset showing no improvement since 2023.The way Health and Social Care services for the have nots in Somerset have developed has become unsustainable, where demand continues to increase as the population becomes older and suffering with more long term and entrenched health conditions.

Whats more, health inequalities in 2035 manifest themselves in a highly visible way in the form of the wearable technology commonly sported by the affluent to enable the monitoring of key health indicators by their private insurers. Amongst the less well-off, this technology is frequently a cause for resentment and envy: many feel that if the NHS had the resources to offer this kind of data-driven monitoring and early-identification of conditions, their parents and grandparents would be able to live longer and more pain-free lives as well.

In Somerset, the number of highly deprived neighbourhoods (categorised as being within the 20% most deprived in England) increased to 45 by 2035 from 29 in 2019, with around 59,000 Somerset residents living in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods. The highest levels of deprivation are found in the countys larger urban areas, with the most deprived area of Somerset being the Highbridge South West area of Sedgemoor. Areas such as Sampsons Wood in Yeovil provide significant points of contrast to deprived communities, falling within the 1% least deprived areas of England.

Indeed, it is also increasingly difficult to ignore the considerable angst amongst the financially precarious majority of younger, working-age people with regards to these widening inequalities. The ironic hashtag #NationalWealthService frequently trends across social media when private providers feature in the news for one reason or another, or form a plot point in one of the UKs popular live-streamed web-based soap operas. More dramatically, the slogan has on several occasions been found emblazoned in red graffiti across the windows of private provider BetterHealths Bristol headquarters, a common locus for protests and community organised demonstrations since its construction in late 2029.

In Somerset, examples of civil unrest are manifested in larger towns from time to time. Although the rioting that has taken place in cities such as Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool and parts of London are not as extreme in Somersets towns, there are common instances of violent attacks on those with visible symbols of wealth, such as those with wearable technology, designer clothing and stylish electric cars, exemplifying a society where those who have not are angered and enraged.

However, discontent with Health and Social Care services is far from limited to private providers. Indeed, even amongst many of the South Wests poorer residents in 2035, these companies are often seen as offering excellent and innovative services, which most would be happy to take advantage of if they had the means to do so. Rather, it is the NHS and state provided social care services which often bear the brunt of popular discontent, whose overworked staff increasingly do not have the capacity to deliver a standard of care and service which members of the public feel they deserve.

Protests are a common occurrence in NHS health care settings, often community led with an increasingly well organised Civilian Protest Army acting as an unregulated force beyond the control of any political party. The group often appear to be verging on anarchy and are motivated by a sense of grievance and exclusion to take random but collective protest action. Leaders of the group are known to police and monitored by the newly established Health Crime Unit based at MI5 as a significant domestic terrorism threat.

This collective rage also shows up in individual consultations with NHS service providers as anger at poor quality services spills over into the waiting room and consulting rooms. High levels of discontent from patients without resources for private care have built up over the past 5 years and have become a defining feature of the interaction between patients and service providers, culminating in 2030 in the high profile, public murder of a young doctor in the entrance of a State Hospital in Somerset. In response, military style security entrances were established in all South West service units by 2032. Services are now organised at scale and in centralised units as a way of managing security threats. Patients are required to prove their identity against an electronic appointment bar; their details are checked against a security database and everyone is body scanned before access is permitted.

Cars are no longer allowed within 300 metres of the security entrance and now have to park in a secure car park managed by a global security company. A pilot wheelchair transport scheme using people serving Community Payback Orders as the workforce is a highly acclaimed but controversial community rehabilitation venture.

The scheme has been rolled out in all South West care settings for people unable to walk from secure car parks to the hospital entrance. The cost of wheelchair transport is high and patients are nervous about being transported by offenders serving Community Payback Orders and even, in some parts of the Region, serving prisoners. As a consequence service demand has been successfully reduced in most settings by 2035 and a contract has been awarded to a combination of newly formed Criminal Justice Units and also the now privatised South West Prison Service for national roll out to all UK health care settings as an exemplar of service innovation.

The migration of more affluent citizens towards private services, meanwhile, has had the effect of gradually diminishing the salience of NHS funding as a crucial issue in determining voter behaviour and satisfaction with the government. Indeed, across many South West areas such as North East Somerset, a growing plurality of the governing parties support base uses private insurance; as they do not tend to come into contact with the NHS, issues such as lengthening waiting times for non-urgent treatment are simply not as high up the priority list for these voters as in decades past.

This has caused many leaders in the sector to worry that future politicians will feel even less constrained in diverting further resources away from statutory Health and Social Care services. Some are concerned that we have now entered a vicious circle: underfunding of public healthcare caused standards of care to decline, pushing more South West residents towards private provision; which in turn decreases the salience of NHS funding as a political issue, paving the way for further cuts to take place.

The role of leadership

In 2035 leaders are recruited, trained and rewarded for two different industries:

- The state NHS system which has replaced the 2020 Health and Social Care system as a low paid, undervalued, second rate career option.

- The private sector which is characterised by a heroic, fast paced and innovative culture where fortunes can be made and awards for new digital solutions are sought after as personal and collective kitemarks.

In the state sector, across the South West health leaders are now primarily managers, responding to centrally determined strategies to be implemented at local level. Clinicians are no longer members of the leadership and management teams in the South West and a separate clinical development programme is run by the private sector to upskill clinicians in digital and technical capabilities.

The state NHS leadership framework has been pared back to five key competencies:

- Financial and business management with a performance emphasis on balancing budgets, reducing service demand and creating financial and human resource surpluses where possible.

- Crisis management - this is prioritised along with financial and business management as the top core competence for NHS leaders today. The Covid pandemic spawned a plethora of research into crisis management in the health and care system, and today all development programmes are underpinned by these competencies. The British Army logistics and emergency response Units have developed a model of Crisis management in partnership with the UK Maxwell Group and UWE have adapted this for a South West leadership programme to equip NHS leaders to deal with any crisis. Influencing skills and negotiation in the context of crisis are foundation level leadership capabilities, particularly with the workforce and with wider healthcare stakeholders such as the private sector who may be able to support.

- Digital and Technical awareness with an emphasis on future scanning capabilities to spot digital care solutions and trends that can ease demand and enable health care to be managed at home rather than in collective centres such as hospitals.

- Personal safety and wellbeing with a focus on personal safety awareness, personal resilience and strict adherence to 35 hour week contracts as the compassionate way to manage overwhelming workloads and performance demands.

- Estate and Security management most NHS Estate is now outsourced to private Facilities Management (FM) companies. This competency is about relationship management with FM companies to ensure that NHS Estate is efficiently maintained and that security remains a high priority. Relationships with the private sector to innovate security solutions is encouraged and a competitive secondment programme to private sector Facilities Management companies has been funded by South West Region to encourage better FM relationships and more partnership solutions.

In the burgeoning private health sector, clinicians and managers are digital tech design and delivery experts or business development specialists. Clinicians are encouraged to innovate and specialise at an early stage of their career and since generalist clinicians are seen as the domain of the NHS they are not encouraged or resourced by the private healthcare industry.

Companies promote a culture of elitism and competition for digital innovation in the workplace and reward behaviours that lead to winning new business or developing digital tech innovations. The recent online recruitment drive for a new generation of clinicians and managers for the South West Regional Healthcare Company described the following attributes and competencies as essential for 2035 graduate and senior staff applicants alike.

Applicants must be able to demonstrate the following -

- Digital awareness, commitment to tech solutions and high level capability with a range of 3D technical design and delivery models.

- Personal attributes that allow comfort with competition, self-reliance, autonomy and decision making - particularly difficult decisions and those that may compromise personal values.

- Ability to ruthlessly focus on digital delivery tasks and targets.

- Ability to remain detached in relation to patient needs, to suspend compassion when required and to focus on business needs as a guiding priority. This is less about encouraging inhuman behaviour and more about ensuring that sentimentalism, moral values and subjectivity dont get in the way of providing innovative digital services that can be accessed by as many people as can pay for it.

Being a patient in the South West in 2035

Josh is 3 and lives in Somerset. Three months ago, after a bout of flu, his Mum suspected that something was amiss. Josh often wet the bed, was constantly thirsty, and was tired and irritable for weeks. Then, one morning, he collapsed. Joshs mum was told there would be up to an hours wait for an ambulance and, after an initial discussion of the phone with the on-call doctor, Joshs Mum drove him to the Accident and Emergency Department at the hospital. After investigation it was discovered that Josh had suffered from Diabetes Type 1 diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). He remained in hospital for two weeks then was referred to the general diabetes service (the specific paediatric diabetes service closed many years ago).

Dr Donnolly, the Diabetes Consultant, talked Joshs family through what Type 1 diabetes was and how it was a lifelong condition that had to be managed constantly. Donnolly looked uneasy as he began to describe the advances in diabetes care in recent years and all the technology that was available on the market. “But, none of the latest genomic treatments, or personal technologies, monitors, closed loop systems, were offered through the NHS”, he explained. “You could only access this kind of support privately,” he said. The Service had been cut back to the bone and despite the increase in Type 1 diabetes in children in the South West, the team had been greatly reduced over the years, with no dietitians. “We really only offer support to families in the initial stages of diagnosis and through quarterly HbA1c tests”.

Donnolly looked cross and explained “across the South West the management of paediatric diabetes tells two stories. The data collected for those who buy the latest medical technologies in diabetes care, show the management of Type 1 diabetes is very good with little evidence of negative outcomes for patients. However, those relying on the NHS for support and outdated insulin pumps find it much harder to manage. The data for that group describes more negative outcomes in later life”.

With no money available to the family and no means to buy the lastest personal technologies, Joshs mum is worried about his future health. They begin a campaign for better state support for children with long term conditions but the first AGM is poorly attended and they abandon the campaign to focus on Josh and his care.

Workforce profile - Somerset

Total workforce size in 2035

The NHS workforce has grown by around a fifth since 2025.

This is not nearly enough to keep pace with the complex demands presented by Somerset's growing population of older people with multiple health needs which has more than doubled since the early part of the 2020s. The western part of Somerset has the oldest age profile in England. However, the overall headcount of the Health and Social Care workforce has grown by a somewhat larger proportion - around a quarter - mainly due to a rapid increase in the popularity of private sector healthcare provision. Once making up only a small fraction of healthcare workers in Somerset, private healthcare now accounts for just over a third of health sector employment in the region whilst catering mainly to the wealthiest fifth of the population.

Workers in the public and private sector tiers in this scenario experience very different working conditions. By 2035, it is clear that one of the most significant long-term impacts of the pandemic and the resultant cost of living crisis of the early 20s has been to exacerbate health inequalities, with the less-well off in Somerset increasingly more likely than the affluent to present with complex issues requiring intense support and experiencing mental health problems such as PTSD. This is the section of the population with which workers in a stretched NHS come into most contact. Staff in the private sector, on the other hand, tend to interact with affluent members of society whose health has improved somewhat in the years since the pandemic, driven in part by the increasing effectiveness of personalised pharmacogenomics-based treatments available to those who can afford it.

These inequalities are also highly geographic in nature - in 2035, most of those in more affluent areas such as well-off parts of Yeovil benefit from private providers offering comprehensive screening services and new, technologically innovative treatment methods to help prevent and ameliorate any problems with their health; while those in more deprived parts of the county such as parts of Sedgemoor tend to have diseases such as cancer and diabetes detected and treated much later by an inadequately funded public tier, with factors causing ill-health including smoking and obesity also remaining stubbornly higher here in comparison to more affluent areas. In addition, accessing a range of AHPs to make positive interventions and impact often depends on geographical and economic factors, where those living in more affluent communities have access to a wider range of paid services.

One of the other main consequences of the growth of the tiered health system has been upon the perceptions of staff working in Somersets Health and Social Care services. While many retain a strong affection to and attachment for the idea of a public health service, the difficulties which the public sector increasingly faces in meeting the health needs of local people, often resulting in visible discontent in waiting and consulting rooms, can make the better pay and less stressful conditions on offer in the private sector tempting to many. Indeed, leaders in Somersets public health services must now reckon with the reality that investing in education, training and professional development of the workforce - while still an absolute necessity if services are to meet the needs and expectations of the public - can also increase the opportunities available to better-qualified staff in the private sector.

In essence, the expectations outlined in the 2023 UK Government’s NHS Workforce Plan have had a mixed and inconsistent impact on how services are delivered.

Fastest growing Health and Social Care occupation

715% increase since 2025

The Personal Health and Wellbeing Specialist (PHWS) has become something of a symbol of the deeply divided Health and Social Care system present in this scenario. Virtually non-existent in the early 2020s - before expanding rapidly in prevalence every year from 2024 onwards - the PHWS has become the most ubiquitous job title amongst Health and Social Care workers employed by the one of the four main private healthcare providers now increasingly present across Somerset. PHWSs are responsible for delivering the personalised care and treatment plans purchased by the growing numbers of affluent citizens who prefer not to rely on a stretched and exhausted NHS. PHWSs also generally take responsibility for monitoring the array of data arising from the wearable technology used by most private healthcare consumers, taking a preventative and proactive approach to protecting the health and wellbeing of clients should this data begin to indicate potential causes for concern.

Other key trends

One consequence of the rise in private provision has been a worsening of recruitment difficulties amongst statutory Health and Social Care services, a situation that was exacerbated by the crippling industrial action and failure to revise salaries in line with soaring inflation and improve working conditions for staff across the health and care sector in the first part of the 2020s. The better pay and conditions and the more flexible working hours on offer in the private health sector make it a tempting destination for NHS workers; private sector health workers are also more likely to be able to benefit from a variety of technological advancements (including 5G and widespread cloud computing) to do more of their work remotely, at home or at another place of their choosing.

To address staffing shortages in the state sector, efforts have been made to make it easier for workers beyond Europe to come to the UK to work for the NHS and in social care, resulting in a workforce which is more ethnically diverse and slightly younger than in decades past. However, under-investment in public services means that the thriving private health care sector remains an attractive option for these workers too, with the result that the NHS continues to have difficulty retaining a workforce of sufficient size and skill to meet the needs of Somersets population in 2035. Although the national government Immigration Policy in the early part of the 2020s was designed to significantly reduce numbers of foreign nationals from entering the country, in the mid to late part of the decade significant exceptions were made to provide increased resources for the state health sector. This has created further tensions in a number of communities across Somerset, where there is increased pressure on areas such as housing and, ironically, the health and care system itself, where increased numbers of immigrants now rely on the actual system in which they work.

Staff survey results

Staff satisfied with their level of pay

down from 38% of NHS staff in 2019

Staff feeling unwell due to work-related stress in the past 12 months

40% in 2019

Staff feel that their manager takes a positive interest in their health and wellbeing

70% in 2019

Staff that often think about leaving their organisation

28% in 2019

Staff that applied for digital training and career development programmes

Staff that have completed digital training and career development programmes

Staff that report low morale and disinterest in work purpose

Impact of Brexit on the workforce

In the post-pandemic years, private healthcare firms sought to boost their workforces (and consequently the standards of care they were able to offer) by making attractive overtures to overseas workers to come and work for them. They offered levels of pay and flexible working conditions which most public Health and Social Care services worldwide were simply unable to match in the mid 2020s. Although the ongoing effects of the pandemic were variable in the UK, the challenges of Covid variants and their impact were still very severely felt in many parts of the world. In Europe, increased tensions due to the war in Ukraine, especially in eastern parts of the continent, meant that many EEA nationals were keen to explore health work opportunities in the UK.

This helped counteract the Brexit effect on EEA migration to the UK, whereby the supply of Health and Social Care workers from EEA countries dried up following the 2016 referendum well in advance of Britains departure from the EU actually being formalised.

Consequently, net migration from EEA countries to work in Health and Social Care in the UK actually began to steadily increase in the years following 2024. The initial terms of Britain's departure from the EU were preventative of migration and movement, but a renegotiation of the UK/EU Treaty in 2024 created routes for EEA migrants to work in areas of the UK where there was an identified need. Still, the fact that overseas recruitment was concentrated disproportionately amongst private firms meant that the overall proportion of the South Wests NHS and social care workforce made up of workers from EEA countries steadily declined throughout the early and mid-2020s, reaching a low of just under 4% in 2028.

Since then, the UK Government has stepped up its efforts to recruit from overseas in order to plug increasingly severe shortages in the NHS and the social care sector, including by mounting advertising campaigns in EEA countries emphasising the UKs continuing cultural similarities with Europe despite Brexit. Nonetheless, while this has had some success in increasing the flow of inwards migration, the NHS and other statutory services now face the difficulty of convincing those workers who have come from overseas to resist the temptation of taking advantage of the higher pay and standards on offer in the UKs private healthcare sector.

The role of clinicians

- Understanding that large corporations drive the development of technology and financing investment in the health sector.

- Increasingly, technological development manages to take over some elements of complex clinical judgement.

- Diagnostic skills are in less demand but they are more likely to be called in to address wicked problems or to make agreements with patients about the next step.

- Doctors provide interventions in NHS settings but that is only the case in private medicine, including surgery, where robotics cannot undertake it.

- Research, innovation and education is more influenced by profits and corporate interests of the big tech companies. They are in the position to choose and fund research projects, and able to select the doctors or hospitals to undertake it.

- Big Technology companies are showing signs of adopting values that are congruent with the NHS model of providing health care.

- There are constant private and public conflicts between the doctors who practise in private and public systems.

- For NHS clinicians, theres an increased focus on influencing skills to manage the resources available as big corporations hold more power around resource allocation than the clinical workforce themselves.

- Whilst some developments have taken place in widening the roles of other health and care professionals and AHPs, the main driver has often been primarily to meet the requirements of corporate health companies rather than patients' needs.

How we got to 2035

Brexit and the United Kingdom leaves the European Union.

The Covid-19 pandemic impacts upon every citizen in Somerset and across the wider UK, with restrictions in England eventually fully lifted in February 2022.

Significant industrial action across the health system and the wider public sector in response to higher inflation, falling real wages and concerns around staff conditions.

UK Covid-19 Inquiry holds first public hearings.

2023 The UK Government publishes its NHS Workforce Plan, setting out independently-verified national-level projections for key job roles over the next 15 years.

General election - the incumbent government loses and opposition parties are invited to form a new Government on a platform to negotiate a new relationship with the EU and introduce a citizens' income.

Community Empowerment legislation is introduced to encourage communities in the South West to take ownership of community assets which are expensive for councils and the NHS to operate, including buildings and public spaces.

European Convention on Human Rights re-enshrined in UK law.

Regional devolution referenda are held and passed by popular vote across England, ultimately turning England into a more federal country.

Those who are willing to pay for it, or are insured, have their genome sequenced routinely.

Creation of waves of new technical jobs with the growing impact of AI.

Voting age for all elections is lowered to age 16.

Introduction of a Citizens' Income and Universal Credit is withdrawn.

Regional assemblies created across England, including the South West, with powers devolved to the local level, based strongly on the principle of subsidiarity. Regional elections held. Local activism and community-led citizen participation increases. The South West elects its first regional Mayor.

The UK joins the European Economic Area (EEA) (on a Norway-plus basis) after four years of intense UK-EU negotiations.

General election - a breakthrough number of Independent MPs representing community interests - building on the strength of their local/regional devolution platforms and supported by the newly enfranchised youth - are elected.

Public murder of young doctor in the entrance of the South West State hospital.

Regional assembly elections held.

Military style security entrances are established in all South West service units.

General election, a Government is formed.